Tarisel Text

Gerard Unger Merit AwardProject overview • Dissertation • Specimen

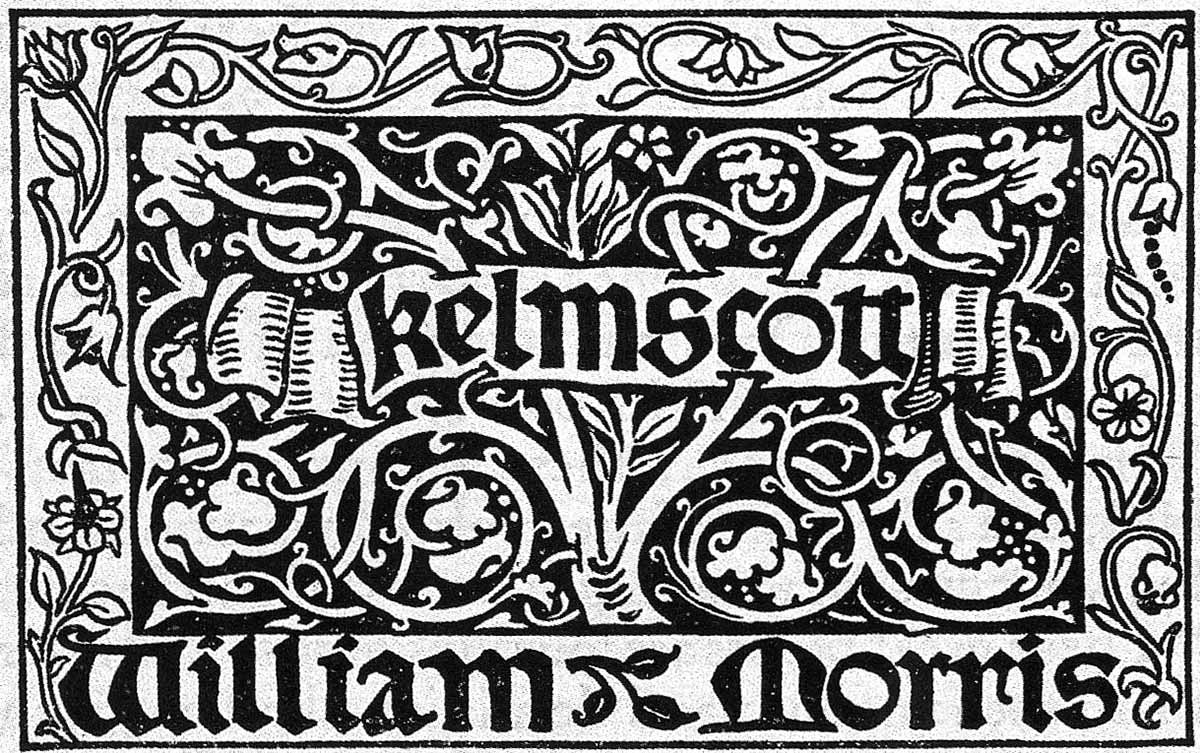

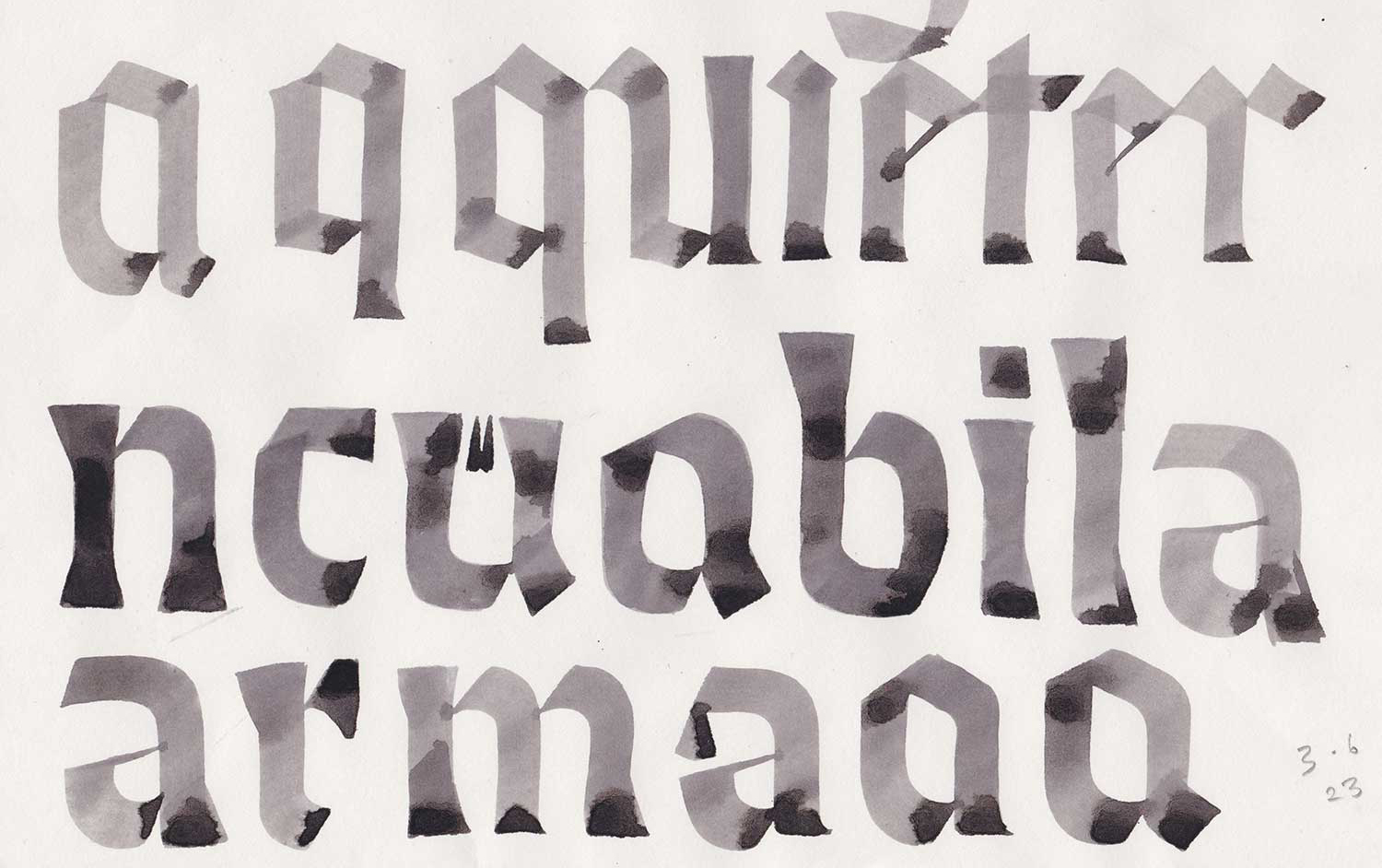

Tarisel Text is the heart of my EsadType graduation project. My goal was to create a hybrid-gothic text typeface that is relevant to contemporary graphic design. In doing so, I sought to translate some of the elements and tone of gothic writing—without falling into any calligraphic clichés.

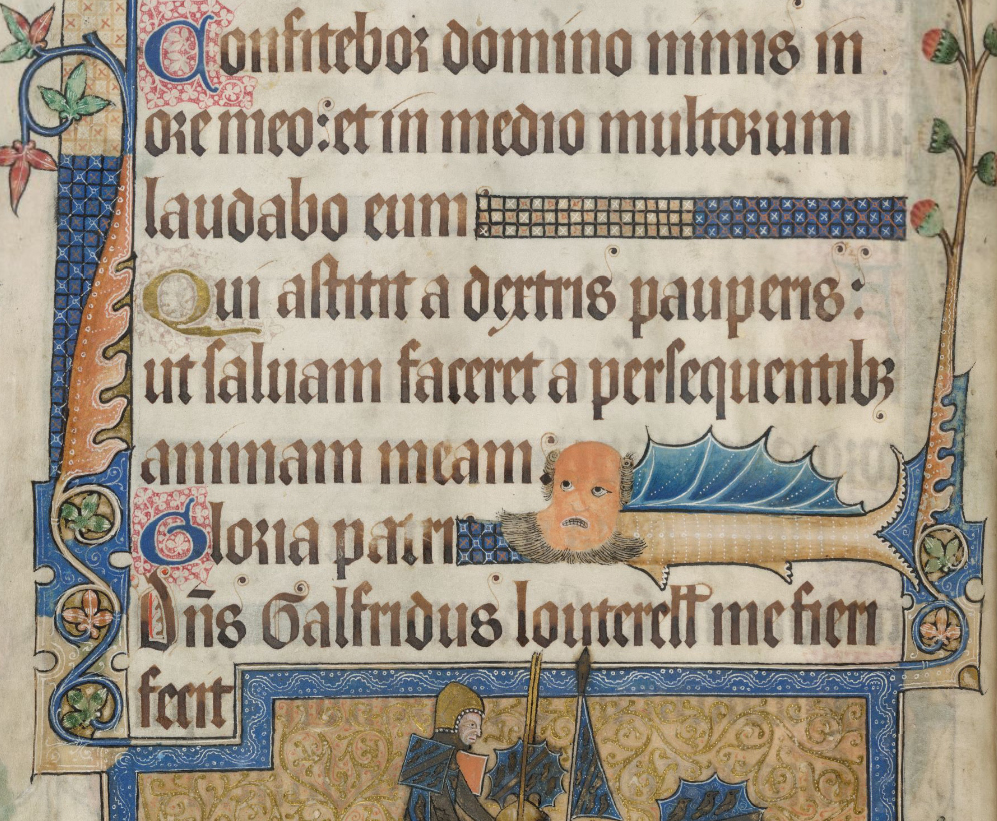

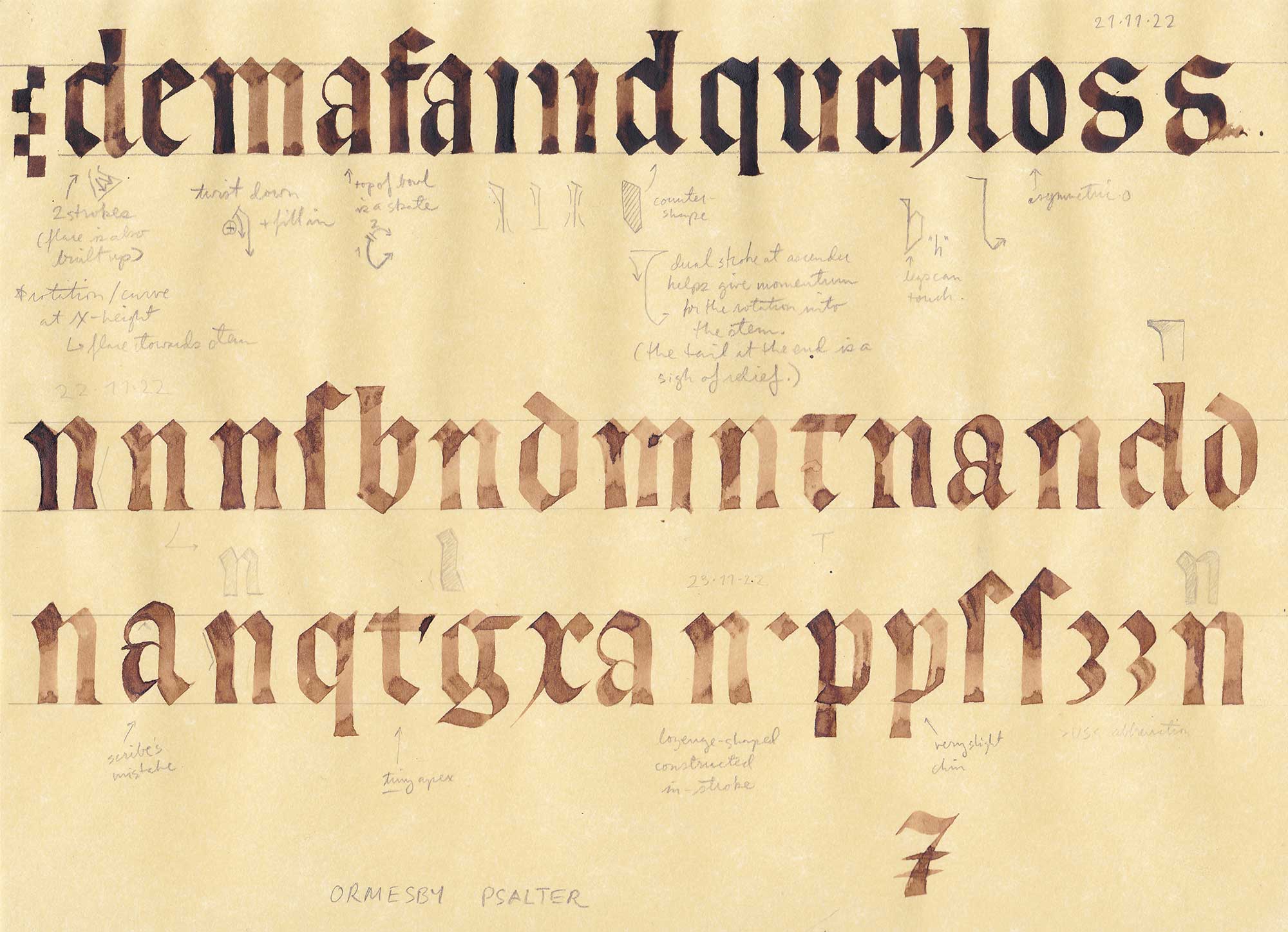

Starting from a particular 13th-century English book hand, Tarisel Text is a hybrid in more ways than one: it bridges gothic and roman, sans and serif, text and display, ancient and modern, making it surprisingly versatile. Over the course of the project, I did a deep dive into a little-known writing style, fell in love with flat brush calligraphy, and found my voice as a type designer. I also learned that there is a lot of ground between gothic and roman styles—so much that this typeface spawned two offshoots: Tarisel Lombardic and Tarisel Hybrid.